At 23-weeks-5-days pregnant, lying in the hospital, Erin, felt her water break. She knew the odds weren’t good for her little boy, arriving four months early. But she saw the confidence in her Neonatologist’s eyes, even as he explained the risks her baby faced. So, she advocated for his life and did everything in her power, to save him (read Erin’s whole story).

A Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) can save babies born way before their 40-week due date—sometimes even as early as 23 weeks. It’s critical for parents of extremely premature babies to understand the process and possible complications, so they can make any decisions needed.

Dr. Robert Gall, MD, the Director of Neonatology at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Burbank, CA, explains the fascinating—and terrifying—steps that go into saving an early preemie:

1. Get the baby breathing.

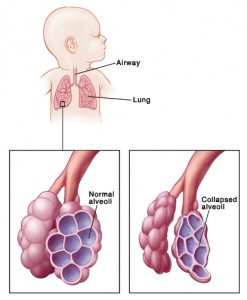

Toward the end of pregnancy, a baby begins to produce surfactant, a substance that coats the lungs. Without surfactant, the alveolar space in the baby’s lungs would collapse when they exhale, leaving them with a breathing problem called Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS). The NICU team injects artificial surfactant to prevent RDS.

They also hook him up to a ventilator, which starts circulating air through his airways.

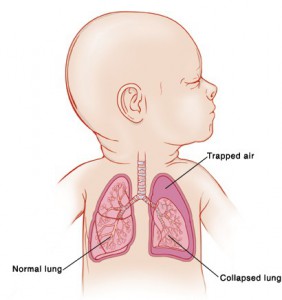

It’s possible for the ventilator to slightly over-inflate a lung, creating a small pinhole, and leading to a collapsed lung (called pneumothorax). This can be corrected by inserting a chest tube to release trapped air, then reinflating the lung.

Once the baby’s breathing, there’s one more step—keeping him breathing. Babies born before about 35 weeks’ gestation, typically breathe a few times, then pause, breathe, pause. But sometimes, after that pause, they “forget” to breathe again, in a condition called Apnea of Prematurity. To prevent this, the NICU gives caffeine, which stimulates breathing.

2. Establish healthy blood flow.

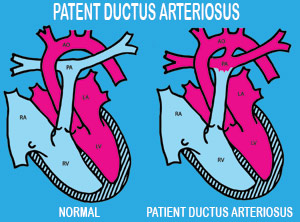

All babies are born with an opening connecting the left and right sides of their heart, a Patient Ductus Arteriosus (PDA). This opening allows blood to take a short-cut between the left and right sides of the circulatory system.

With healthy full-term babies, the connection closes within the first 24-48 hours. With preemies, however, the connection doesn’t close on its own. As blood continues to take a short-cut, the blood vessels around the lungs become pressurized and start to leak fluid into the lungs, in a condition known as Congestive Heart Failure (CHF). The NICU prevents this cycle by injecting the babies with Indomethacin, on their first day, which closes the ductus in about 80% of cases. In the remaining cases, doctors can surgically close the PDA.

3. Avoid infection.

Preemies are extra-prone to infection. A mother starts to pass her antibodies to a baby at 32 weeks pregnant. Babies born before that, though, don’t have any of mom’s defenses. There’s also a lot of invasive monitoring and treatment (e.g.: central line and ventilator) in place for a preemie, which can introduce infection. And, if the amniotic sac broke more than 18 hours before delivery, risk of infection is even higher.

Last, a very early preemie’s skin is gelatinous at birth. If someone touched his skin or put tape on it, the skin would come off. Damaged skin makes him more prone to infection. The NICU gets around this by using the umbilical artery for the IV and wrapping him in plastic wrap until his skin becomes more firm.

Because of the high infection risk, the NICU staff gives antibiotics like Vancomycin, Gentamicin and/or Cefotaxime.

4. Keep the baby stable… and PRAY for no Intra-Cranial Hemorrhage (ICH)

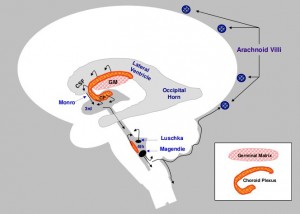

Prior to 32 weeks gestation, a baby’s brain contains a very fragile structure called the Germinal Matrix (GM)—if it bleeds, it can cause serious brain damage.

A brain bleed can be triggered by the same medical conditions doctors are already tackling, like Respiratory Distress Syndrome and unstable blood pressure.

If doctors see evidence of a bleed, they use an ultrasound to assign the ICH one of four grades: I) blood just within the GM (pretty common), II) blood escapes from the GM into the ventricle, III) blood causes the ventricle to dilate, and IV) blood escapes the ventricle and destroys surrounding brain tissue. Babies who have grade I or II bleeds generally do very well. With a grade III bleed, there’s about a 60% chance of mental retardation and cerebral palsy; with a grade IV, there’s about a 90% chance.

If a serious bleed happens, parents have to make a very difficult choice. Their first option is to continue to take every measure possible to keep the baby alive. Babies often accommodate for their injuries, but require life-long care. Most need a feeding tube and never walk, talk or meaningfully interact with the family… and that full-time obligation tears apart many families. The next option is Do Not Resuscitate (DNR). With this option, the hospital continues life support, but if the baby crashes, they don’t perform CPR–they let nature take its course. The baby could crash at a time when the family can’t get there in time, though… or he may not crash at all, and the window may pass for making this decision. The third option is terminal extubation (removing life support). This is the heart-breaker, but there’s a beauty and courage to this option too. Parents take their baby to a quiet room and get to hold him in their arms, enjoy him, and shower him with love, for a little while as he passes.

The good news is that 98% of all bleeds happen within the first four days, so a baby just needs to hang on for a few days. “If I can get you through the first week, I know I can get your lungs better”, Dr. Gall insists. “I know I can get your PDA closed, because even if it doesn’t close with medication, I can surgically ligate it. If I’m on top of it, antibiotics will cure your infection… If I can get you through the first seven days without a major complication, you’re going to be OK.”

So, there really is hope, for these super-early babies.

As for Erin’s very early arrival… she delivered Jayden, who weighed less than 1½ lbs (680 grams) at birth. He had a minor brain bleed and spent 91 days in the NICU.

But he made it. Today, he’s a healthy 2-year-old. “He’s perfect,” shares Erin, “He was a frog for Halloween”.

- – -

Preemie parents—you’re not helpless! Here are four really important ways you can help:

- Provide breastmilk. Breastmilk passes antibodies to your baby to help prevent infection. Especially with preemies, breastmilk also helps to protect your baby’s gut from a serious disease associated with cow-based milk (like formula) called Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC). So pump those breasts and meet with a lactation consultant!

- Give kangaroo care. Once your baby is ready, holding him skin-to-skin helps with your bond, improves his health, and promotes brain plasticity.

- Offer Occupational Therapy/Physical Therapy (OT/PT): Experts give babies little exercises, adjust their position, help them learn to eat, and help you learn to feed them.

- Choose your hospital wisely. Plan to deliver at a hospital with a NICU, lactation support, and OT/PT just in case.

Thanks so much to Dr. Gall for sharing all of this information with me so I could share it with you. Thanks also (again) to Erin for sharing her story. If you enjoyed this article and you’d like to see more from Mama Lovejoy, you can “like” my Facebook page or check out www.mamalovejoy.com. You can follow @MamaLovejoy1 on Twitter, Instagram or Tumblr. Thanks!!